Presented by: Chrysa Koutsiouki MD

Edited by: Penelope Burle de Politis, MD

A 41-year-old man was referred for severe recurrent bilateral anterior uveitis poorly responsive to topical treatment.

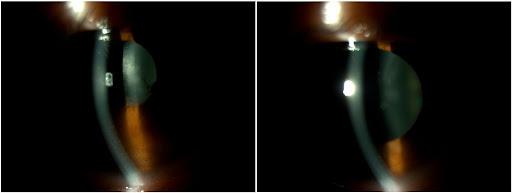

Figure 1: Slit-lamp photograph displaying bilateral keratic and lenticular precipitates, as well as posterior synechiae in the right eye.

Case History

A 41-year-old Caucasian man of Greek descent was referred for investigation of severe recurrent bilateral anterior uveitis for 3 months (Figure 1). He had been on treatment with topical dexamethasone 0.1%, with some response only while instillation was under 2-hourly. He reported nonspecific joint soreness and a few skin rashes on his face, but no back pain, oral or genital ulcers, nor genitourinary or gastrointestinal issues. There was no history of cough or shortness of breath, weight loss, night sweats, pins and needles’ sensation, nor contact with tuberculosis.

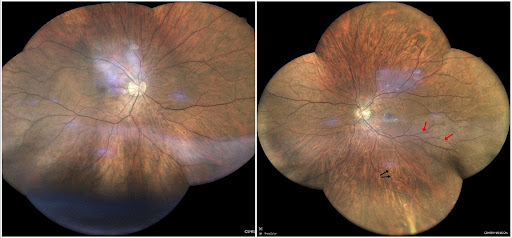

Distance corrected visual acuity (DCVA) was 10/10 bilaterally, with respectively -4.50 and -5.00 spherical diopters in the right eye (RE) and left eye (LE). IOP was 20 mmHg in both eyes (BE). At biomicroscopic examination, there were pigmented keratic precipitates (KP), anterior chamber cell reaction of 2+ and flare of 1+ bilaterally. There were posterior synechiae from 4 to 8 hours of the iris border in the RE and a ground-glass appearance of both crystalline lenses. Fundus findings in BE were a mild vitritis, a hyperemic optic disc (more evident in the RE), yellowish preretinal dots at the inferior quadrant, and discrete vascular sheathing suggestive of periphlebitis (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mosaic display of confocal high-resolution widefield imaging (iCare EIDON®) showing a “hot” disk and pale yellowish perivascular preretinal dots at the end of the inferior temporal arcade and mid-periphery (black arrows), and mild sheathing of temporal vessels (red arrows) in both eyes.

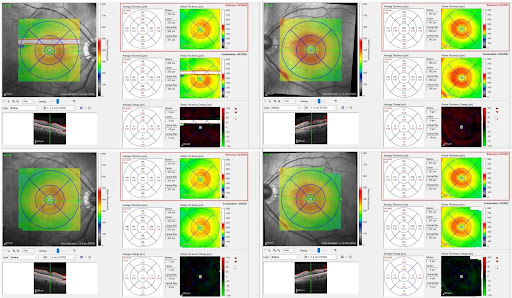

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) evidentiated bilateral subclinical macular edema, more pronounced in the RE (Figure 3, top images). The retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) was normal in BE.

While the retinal changes accompanying the anterior inflammation were still subtle, the impression drawn was of a bilateral subacute panuveitis in an exacerbation phase. Instillation of the dexamethasone drops was increased to hourly and tropicamide b.i.d. was added to the regimen. A systemic workup was requested, and the patient was scheduled for a review 10 days later.

Additional History

The patient had been diagnosed HIV-positive for about a year and was in use of darunavir/ritonavir and dolutegravir with regular follow-up by the specific clinic. He had a recent CD4+ count of 400 cells/mm3 and a viral load of 20 copies/mL. Systemic workup results showed a slight megaloblastic anemia as pointed out by the RBC (3.94 mi/mm3), MCH (34.5 pg) and MCV (103.8 fL) indexes. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 60 mm/h. QuantiFERON™-TB, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and HLA-B27 were negative, and the thorax CT was normal. The venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test was negative. However, both fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) IgM and IgG were positive (respectively 1/10 and 1/40). C-reactive protein (CRP) was at 0.83 mg/dL (N<0.5 mg/dL).

Upon review, inflammatory signs were partially resolved, with pigmentation of the KP in the RE and reduction of the anterior chamber cell reaction to 1+ in the LE. However, in the face of the laboratory results, the diagnosis was updated to syphilitic bilateral uveitis associated with HIV infection, thus requiring referral to a sexual health / genitourinary medicine (SHC or GUM) clinic for treatment and monitoring.

The patient was started on IM penicillin – route of patient’s choice – and presented for a review 2 weeks later with worsening of the inflammation in the LE, noticed as newer KP and increased anterior chamber cell reaction to 2+. Fundus findings were unchanged, but OCT revealed a slight increase in the macular edema in that eye. Considering the signs of imminent deterioration, therapy was discussed with the GUM Clinic staff, who agreed to the initiation of oral prednisone starting at 40 mg/day and weekly tapering. Omeprazole was prescribed as well. Dexamethasone drops were taken back to every 2 hours.

Two weeks later and after the 5th penicillin injection, there was subjective improvement in vision, and the joint soreness and skin rashes had subsided. There were no longer signs of anterior uveitis in either eye, pigmented KP had resolved almost entirely and the iris in the RE was 360° free. OCT findings were improving as well (Figure 3). The patient was examined again 4 weeks later and remains stable.

Figure 3: Spectralis SD-OCT (Heidelberg Engineering®) thickness map illustrating bilateral subclinical macular edema, with more increased thickness in the RE (average reaching 400 μm in the nasal quadrant before treatment – top right). Bottom right: RE after treatment (average thickness in the nasal quadrant dropping to 359 μm). Left: LE before treatment (top), average thickness reaching 393 μm in the nasal quadrant and dropping to 374 μm after treatment (bottom).

Differential Diagnosis of Recurrent Uveitis in Adults:

- sarcoidosis

- infections (syphilis, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, bartonellosis, brucellosis, herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus)

- HLA-B27-associated diseases (ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease)

Identification of the predominantly involved location can narrow the differential. Posterior uveitis is more commonly associated with an infectious cause. Syphilis and tuberculosis should be excluded in all uveitis cases. Immunodepression can be associated with any form of uveitis. In immunocompromised patients, an infectious etiology is much more likely than in immunocompetent ones.

Discussion and Literature

Syphilis is a common worldwide sexually transmitted infection transmitted via oral, anal and vaginal intercourse. Congenital syphilis refers to vertical transmission of the etiological agent, the spirochete Treponema pallidum, from mother to fetus transplacentally during pregnancy. Syphilis can infect any organ, with complex and variable manifestations that can mimic many other inflammatory, infectious or autoimmune diseases, thus being called “the great impostor”, “the great masquerader” or the “great imitator”.

Since the use of penicillin in the mid-20th century, the spread of syphilis has been largely controlled, although efforts to eradicate it entirely have been unsuccessful. The disease has increased exponentially in the United Kingdom, Europe, United States, and Asia over the past decade and poses a significant public health problem. Demographic data vary among studies according to social and cultural factors and the stigma around sexually transmitted diseases, which makes under-reporting a possibility. Diagnosis in the early stages is key, since the condition is treatable and, if left untreated, can result in permanent sequelae.

Typically, syphilis presents in the waxing and waning phases of the disease and, when untreated, can progress through four defined stages: primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary syphilis. Primary syphilis is characterized by a chancre at the site of inoculation. Secondary syphilis classically presents as a macular rash with generalized lymphadenopathy as a result of hematogenous dissemination. Tertiary syphilis can affect virtually any system of the body and is often devastating to the patient. T. pallidum disseminates to the central nervous system within days after exposure. While the majority of cases are treated before they progress to late stages, studies suggest rates of neurosyphilis are as high as 3.5%.

Ocular syphilis refers to the group of inflammatory eye diseases that result from infection of the ocular tissues with T. pallidum and affects about 1% of those with early syphilis. Ocular manifestations can occur at any stage of the disease and may involve any ocular structure, from the anterior segment, lens, uveal tract, retina and retinal vasculature, to the optic nerve, cranial nerves and pupillomotor pathways. Primary ocular syphilis can manifest as chancres on the eyelid or conjunctiva. Reported ocular signs of secondary syphilis include scleritis, keratitis, anterior uveitis, posterior uveitis, panuveitis, vitritis, chorioretinitis, and necrotizing retinitis. Inflammation is bilateral in most patients. The most frequently reported ocular manifestation of tertiary syphilis is bilateral diffuse periostitis.

Syphilis may lead to any type of intraocular inflammation. Uveitis accounts for most cases of ocular syphilis, but diverse forms of anterior, intermediate, posterior and panuveitis have been described. The most frequent form of intraocular inflammation in syphilis is panuveitis, the posterior segment being inflamed in 90% of eyes. The most frequent posterior manifestations are vitritis (85%), followed by retinal involvement (76%) and optic disc abnormalities (63.5%). Isolated anterior uveitis is rare and 96% of patients presenting with isolated anterior uveitis are HIV-positive. Optic nerve involvement occurs in 78% of patients, most commonly as inflammatory disc oedema, a more frequent finding in HIV-positive patients comparatively to HIV-negative, apparently with a preference for the left eye though the cause is unknown.

Syphilitic uveitis is rising in incidence in tandem with the continuing overall rise of early syphilis in Europe, with peaks in 2005 and between 2010 and 2014, the highest index in 7 decades. Epidemiology has been influenced by factors that include high-risk sexual practices and global travel, immunomodulatory impacts of infection with HIV and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), and changes in antibiotic sensitivity of T. pallidum. Almost all patients are men, more frequently middle-aged, and most are men who have sex with men (MSM). A high level of vigilance in undertaking relevant history-taking for associated risk factors and symptoms is important, since early diagnosis and treatment usually leads to a good visual outcome.

The clinical findings of syphilitic uveitis are highly diverse and nonspecific. Characteristic presentations include acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis (ASPPC) and syphilitic punctate inner retinitis. Preretinal pale yellowish dots located in the vitreous-retina transition, mainly overlying vasculature and in the periphery are considered characteristic and highly suggestive of ocular syphilis. However, due to the lack of pathognomonic signs and to the fact that uveitis may be the first (and even sole) manifestation of the disease, a high index of suspicion is essential for a definite diagnosis. A triad of headache, red eye or eye pain, and elevated ESR should raise clinical suspicion for ocular syphilis, yet syphilis tests should be routinely performed in all patients with uveitis, retinitis, optic neuritis, or optic atrophy.

The VA at presentation of ocular syphilis can vary and reflects the presence or absence of direct macular involvement or the severity of panuveitis. Visual improvement or complete recovery is possible in most cases with early antimicrobial treatment. Factors associated with final visual acuity ≤ 1.0 despite therapy are worse initial VA, delayed treatment, longer duration of symptoms, higher VDRL titers, presence of HIV coinfection, concomitant neurosyphilis, and inadvertent use of systemic corticosteroids prior to the definite diagnosis. Structural damage to the optic nerve and retina is the main cause of permanent visual loss. It is important to notice that patients may go a long way with low or even falsely negative VDRL titers in up to 30% of cases. FTA-ABS or MHA-TP are more sensitive and specific but provide no indication of disease activity.

Syphilis is an important facilitator of HIV transmission with currently reported co-infection rates of 50-70%, not related to immune deficiency but rather to the same route of infection. The presence of HIV may alter the presentation of syphilis, with possibly a more rapid progression to neurosyphilis. People living with HIV (PLWH) have a 77 to 86 times higher chance of being co-infected with syphilis than HIV-negative individuals. Ocular syphilis remains one of the common causes of bacterial infection in HIV-positive patients.

Ocular complications occur in up to 70-80% of untreated HIV-infected patients, and more than half of these are associated with intraocular inflammation or uveitis. The specific immune condition of patients infected with HIV makes diagnosing HIV-related uveitis difficult. Uveitis is one of the most common ocular complications in PLWH and can be classified into HIV-induced uveitis, co-infection related uveitis, drug-induced uveitis, and immune recovery uveitis (CMV-related). The introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has considerably changed the incidence, diagnosis, and treatment of different types of HIV-related uveitis. Paradoxically, the incidence of ocular syphilis has continuously increased since the combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) era.

As with all patients with uveitis, the approach to the HIV-positive patient with intraocular inflammation should start with a complete history and review of systems. This should include the duration of HIV disease, recent measurements of CD4+ cell count and HIV load, current medications, and any history of other sexually transmitted infections or AIDS-defining illnesses or complications. An immunocompromised state has been found in 13% of uveitis patients, 23% of which are HIV-related. Syphilis infection in HIV-infected men has been associated with a significant increase in the HIV viral load and a significant decrease in the CD4 cell count. However, syphilitic uveitis can occur with any CD4 counts and in virtually any stage of syphilis (primary, secondary, or latent), although it is more commonly seen in secondary syphilis.

Given that the eye is an extension of the central nervous system, ocular syphilis is best regarded as neurosyphilis, with possible associated central nervous system involvement. In fact, the presence of uveitis is one of the criteria of early neurosyphilis in the clinicopathological classification of neurosyphilis symptoms, defined by symptoms of decreased vision, eye pain or photophobia, with diagnosis confirmed by slit-lamp examination. The 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend that ocular syphilis be treated as neurosyphilis, regardless of the stage of clinical presentation or of lumbar puncture results, with intravenous (IV) crystalline penicillin G, 24 million international units per day, for 10-14 days or longer depending on the patient’s status. In case of penicillin allergy, doxycycline or erythromycin can be used as an alternative, not as effective treatment. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, a transient phenomenon resembling bacterial sepsis, usually starting 6 to 8 hours after the initial anti-spirochete treatment, can present as worsening of ocular signs.

There are no controlled studies proving the benefits of adjunctive systemic corticosteroid treatment for syphilitic uveitis. However, timely administration of oral corticosteroids has been shown to be effective in controlling posterior inflammation in ocular syphilis. Alternatively, it can be added if the initial IV penicillin treatment is not followed by an improvement in ocular signs and/or visual function. Periocular dexamethasone injections and methylprednisolone pulses are not indicated as they negatively affect the outcomes. Oral methotrexate (MTX) has also been reported to be beneficial as an adjunctive therapy for ocular syphilis in resolving residual intraocular inflammation and cystic macular edema (CME). HAART does not prevent the occurrence of ocular syphilis but can help early resolution along with definitive anti-syphilitic treatment.

Keep in mind

- Syphilis is on the rise, especially, but not only, in people living with HIV. All uveitis patients (HIV-positive included) must be tested for syphilis.

- Syphilitic uveitis must be regarded as neurosyphilis, since it is often accompanied by retinitis and ocular nerve involvement, both of which are risk factors for adverse outcomes.

- Early diagnosis and treatment of ocular syphilis with parenteral penicillin are crucial for rapid recovery and prevention of permanent visual loss.

References

- Mathew RG, Goh BT & Westcott MC (2014). British Ocular Syphilis Study (BOSS): 2-year national surveillance study of intraocular inflammation secondary to ocular syphilis. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 55(8), 5394–5400. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-14559

- Wells J, Wood C, Sukthankar A & Jones NP (2018). Ocular syphilis: the re-establishment of an old disease. Eye (London, England), 32(1), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.155

- Lee MI, Lee AW, Sumsion SM & Gorchynski JA (2016). Don’t Forget What You Can’t See: A Case of Ocular Syphilis. The western journal of emergency medicine, 17(4), 473–476. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2016.5.28933

- Rothova A, Hajjaj A, de Hoog J, Thiadens AAHJ & Dalm VASH (2019). Uveitis causes according to immune status of patients. Acta ophthalmologica, 97(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13877

- Furtado JM, Arantes TE, Nascimento H et al. (2018). Clinical Manifestations and Ophthalmic Outcomes of Ocular Syphilis at a Time of Re-Emergence of the Systemic Infection. Scientific reports, 8(1), 12071. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30559-7

- Klein A, Fischer N, Goldstein M, Shulman S & Habot-Wilner Z (2019). The great imitator on the rise: ocular and optic nerve manifestations in patients with newly diagnosed syphilis. Acta ophthalmologica, 97(4), e641–e647. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13963

- Queiroz RP, Inês DV, Diligenti FT et al. (2019). The ghost of the great imitator: prognostic factors for poor outcome in syphilitic uveitis. Journal of ophthalmic inflammation and infection, 9(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12348-019-0169-8

- Yang M, Kamoi K, Zong Y, Zhang J & Ohno-Matsui K (2023). Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Uveitis. Viruses, 15(2), 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15020444

- Cunningham ET Jr (2000). Uveitis in HIV positive patients. The British journal of ophthalmology, 84(3), 233–235. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.84.3.233

- Joyce PW, Haye KR & Ellis ME (1989). Syphilitic retinitis in a homosexual man with concurrent HIV infection: case report. Genitourinary medicine, 65(4), 244–247. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.65.4.244

- Lee SY, Cheng V, Rodger D & Rao N (2015). Clinical and laboratory characteristics of ocular syphilis: a new face in the era of HIV co-infection. Journal of ophthalmic inflammation and infection, 5(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12348-015-0056-x

- Sudharshan S, Nair N, Curi A, Banker A & Kempen JH (2020). Human immunodeficiency virus and intraocular inflammation in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy – An update. Indian journal of ophthalmology, 68(9), 1787–1798. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_1248_20

- Buscho SE, Ishihara R, Gupta PK & Mopuru R (2022). Secondary Syphilis Presenting as Bilateral Simultaneous Papillitis in an Immunocompetent Individual. Cureus, 14(8), e28465. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.28465

- Mohd Fadzil NI, Abd Hamid A, Muhammed J & Hashim H (2022). Ocular Syphilis: Our Experience in Selayang Hospital, Malaysia. Cureus, 14(7), e26655. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.26655

- Sahin O & Ziaei A (2015). Clinical and laboratory characteristics of ocular syphilis, co-infection, and therapy response. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.), 10, 13–28. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S94376

- Sittivarakul W, Aramrungroj S & Seepongphun U (2022). Clinical features and incidence of visual improvement following systemic antibiotic treatment in patients with syphilitic uveitis. Scientific reports, 12(1), 12553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16780-5

- Sun CB, Liu GH, Wu R & Liu Z (2022). Demographic, Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of Ocular Syphilis: 6-Years Case Series Study From an Eye Center in East-China. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 910337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.910337

- Balamurugan S, Gurnani B & Kaur K (2020). Commentry: Ocular coinfections in human immunodeficiency virus infection – What is so different? Indian journal of ophthalmology, 68(9), 1997–1998. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_680_20

- Bollemeijer JG, Wieringa WG, Missotten TO et al. (2016). Clinical Manifestations and Outcome of Syphilitic Uveitis. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 57(2), 404–411. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-17906

- Rodrigues RA, Nascimento HM & Muccioli C (2014). Yellowish dots in the retina: a finding of ocular syphilis?. Arquivos brasileiros de oftalmologia, 77(5), 324–326. https://doi.org/10.5935/0004-2749.20140081

- Gu X, Gao Y, Yan Y et al. (2020). The importance of proper and prompt treatment of ocular syphilis: a lesson from permanent vision loss in 52 eyes. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV, 34(7), 1569–1578. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16347

- Daey Ouwens IM, Ott A, Fiolet A et al. (2019). Clinical Presentation of Laboratory Confirmed Neurosyphilis in a Recent Cases Series. Clinical neuropsychiatry, 16(1), 17–24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8650203/