Presented by: Evangelos Lokovitis MD, FEBOphth

Edited by: Penelope de Politis, MD

A 36-year-old woman presented with a lump on the right upper eyelid for 3 months.

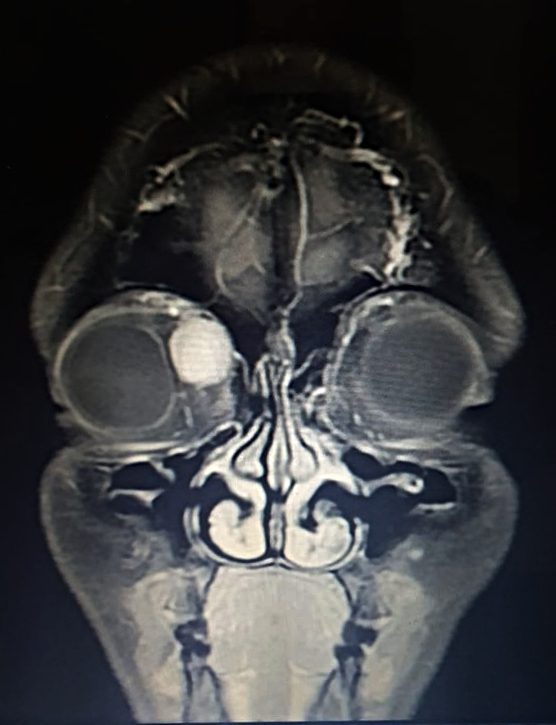

Figure 1: Coronal magnetic resonance T1-weighted imaging (T1-MRI) of the skull.

Case History

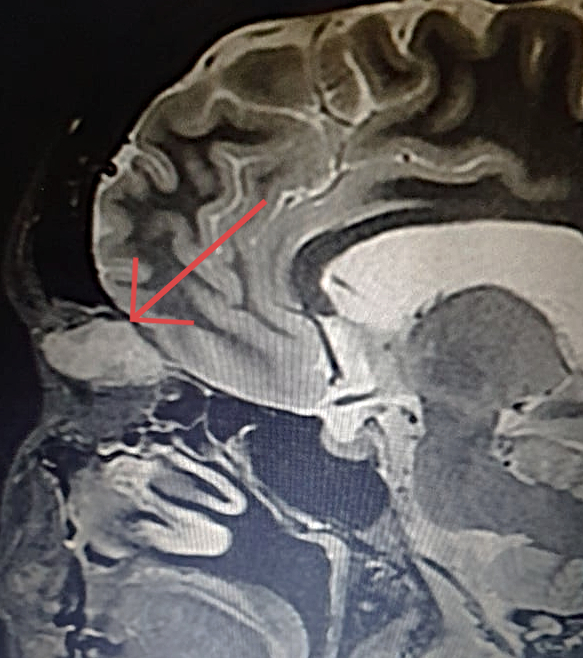

A 36-year-old Caucasian woman was referred for a progressively enlarging painless engorgement at the medial corner of the upper right lid for 3 months. She had sought an ophthalmologist 6 months before, for disturbances in bilateral vision, with no significant findings. On examination, uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was 10/10 on each eye, but the complaint of poor stereopsis persisted. Fundoscopy was bilaterally normal. Intraocular pressure was 19 mmHg on the right and 14 on the left eye. There were neither signs of inflammation, nor ulcers or scars. A slight lateral deviation was noticeable on the right eye. Exophthalmometry was negative, as was the flashlight test for relative afferent pupillary defect. Palpation of the eyelid denoted a soft, slightly mobile mass, painless on retropulsion, with no detectable pulse or bruit. Imaging investigation with MRI of the skull displayed an orbital mass of rather homogenous hyperintensity, superomedial to the ocular globe, not disrupting contiguous structures (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2: Coronal T1-weighted MRI of the skull showing a hyperintense cone-shaped mass at the superior-medial aspect of the orbit, with small patches of hypointensity (arrow). The orbital walls are intact and there is no intraconal involvement.

Surgery for excisional biopsy was indicated and the surgical approach disclosed a well-circumscribed, encapsulated, thoroughly resectable tumor, not compromising adjacent structures. The lesion measured 2.7 X 1.7 cm and had a complete, smooth, translucid capsule and slightly lobulated structure. Vascularization was prominent, but there was no evident bleeding nor macroscopic signs of necrosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Macroscopic aspect of the resected mass, a cone-shaped tumor with a whitish-colored outline and elastic texture, measuring 2.7cm in the largest axis.

Under microscopic examination, the neoplasm consisted predominantly of bundles of spindle cells with elongated, deep-colored nuclei (highly cellular, solid areas), alternated with areas of modest cellularity without visible nuclei (non-pigmented), in an irregular arrangement over a substrate of loose myxoid connective tissue.

Additional History

The patient had delivered a child one year before. She also had a history of surgery for strabismus sometime during childhood. There were no other lumps in any part of her body and her remaining medical records were unremarkable.

Differential Diagnosis

- orbital schwannoma

- neurofibroma

- malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors

- meningioma

- cavernous hemangioma

- lymphangioma

- fibrous histiocytoma

- lymphoma

- dermoid cyst

- hemangiopericytoma

- pleomorphic adenoma of the lacrimal gland

Definitive diagnosis of an orbital neoplasm requires biopsy. It is nearly impossible to differentiate between these tumors based on clinical exam alone. Cellular architecture alternating two distinct patterns — solid cellular areas and areas of loose microcystic tissue — is typical of schwannomas.

Discussion and Literature

Schwannoma, also called neurilemmoma, is a benign neoplasm, relatively rare, originating from the Schwann cells that form the myelin sheath around peripheral nerves. It may occur anywhere in the body, but the usual site of occurrence is the head or neck. In the ophthalmic area, it usually presents in the orbit. Schwannomas occur mainly in individuals aged between 20 and 50 years and account for only 1–2% of all orbital tumors. There is no side or gender predilection.1

Orbital schwannomas most commonly arise from the supratrochlear or supraorbital branch of the trigeminal nerve, although identification of the nerve of origin is not always possible. Due to their indolent behavior, such masses may grow over the course of many years2, until complications arise in the form of compression, dislocation or disruption of adjacent structures, usually manifesting by exophthalmos, optic neuropathy, diplopia, anterior orbital mass or sinusitis.3 Tumor with intracranial extension may give rise to neurologic repercussions.

Although computerized tomography and ultrasonography may be of aid, magnetic resonance imaging is the method of choice for suspected orbital schwannomas, because of its high sensitivity, especially when contrast is used for signal enhancement. In a large review of 62 confirmed cases over 7 years, the cone-shaped lesions were the most frequent, followed by dumbbell-shaped, oval and round lesions. The superior aspect of the orbit was the most common site, followed by the medial superior and the orbital apex.4

Diagnostic certainty is attained through excision of the tumor and histopathologic analysis. Surgical resection must be performed through the most accessible, least invasive route, under general anesthesia. For lesions presenting anteriorly, a transconjunctival or transcutaneous approach is the access of choice. Schwannomas confined to the orbit can usually be entirely removed, with good outcomes.5, 6 Larger masses extending intracranially need a multispecialty procedure. The microscopic arrangement of schwannomas typically displays two distinct patterns: a fibrillary, elongated, highly cellular tissue type, called “Antoni A”, and a soft mucinous background, known as “Antoni B”.7 Immunohistochemistry is a useful adjuvant when pathology is doubtful, notably for the expression of protein S100.8

In most cases, schwannomas manifest as a single neoplasm. The presence of multiple growths is usually indicative of neurofibromatosis type 1 or 2. Despite the unlikelihood of a schwannoma in the orbit, considering it in the differential diagnosis of well-circumscribed, slow-growing tumors is of ultimate importance, since total removal, with preservation of orbital anatomy, is possible even for long-standing disease. Radiotherapy is an option for cases not allowing full surgical elimination. The recurrence rate after complete excision is low and malignant transformation is extremely rare,9 but long-term follow-up is advised.10

Keep in mind

- Any unilateral engorgement in the orbital area should be examined and managed by a qualified professional.

- Orbital tumors vary widely in nature. Proper investigation can allow early treatment and better prognosis.

- Schwannomas of the orbit may have aesthetic and/or functional implications, but surgical intervention can be curative in most cases.

References

- Chen, M. H., & Yan, J. H. (2019). Imaging characteristics and surgical management of orbital neurilemmomas. International journal of ophthalmology, 12(7), 1108–1115. https://doi.org/10.18240/ijo.2019.07.09.

- Konrad, E. A., & Thiel, H. J. (1984). Schwannoma of the orbit. Ophthalmologica. Journal international d’ophtalmologie. International journal of ophthalmology. Zeitschrift fur Augenheilkunde, 188(2), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1159/000309352.

- Rootman, J., Goldberg, C., & Robertson, W. (1982). Primary orbital schwannomas. The British journal of ophthalmology, 66(3), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.66.3.194.

- Wang, Y., & Xiao, L. H. (2008). Orbital schwannomas: findings from magnetic resonance imaging in 62 cases. Eye (London, England), 22(8), 1034–1039. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702832.

- Yong, K. L., Beckman, T. J., Cranstoun, M., & Sullivan, T. J. (2020). Orbital Schwannoma-Management and Clinical Outcomes. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery, 36(6), 590–595. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000001657.

- Kim, K. S., Jung, J. W., Yoon, K. C., Kwon, Y. J., Hwang, J. H., & Lee, S. Y. (2015). Schwannoma of the Orbit. Archives of craniofacial surgery, 16(2), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2015.16.2.67.

- Wippold, F. J., 2nd, Lubner, M., Perrin, R. J., Lämmle, M., & Perry, A. (2007). Neuropathology for the neuroradiologist: Antoni A and Antoni B tissue patterns. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology, 28(9), 1633–1638. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A0682.

- Bagaglia, S. A., Meduri, A., Inferrera, L., Gennaro, P., Gabriele, G., Polito, E., Fruschelli, M., Lorusso, N., Tarantello, A., & Mazzotta, C. (2020). Intraconal Retro-Orbital B-Type Antoni Neurinoma Causing Vision Loss. The Journal of craniofacial surgery, 31(6), e597–e599. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000006726.

- Chang, B. Y., Moriarty, P., Cunniffe, G., Barnes, C., & Kennedy, S. (2003). Accelerated growth of a primary orbital schwannoma during pregnancy. Eye (London, England), 17(7), 839–841. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700475.

- Sweeney A, Burkat CN, Stewart K, Lee V. American Academy of Opthalmology. Orbital schwannoma. www.eyewiki.org/Orbital_schwannoma.