Presented by:

Lampros Lamprogiannis MD, MSc, PhD, FEBOphth

Solon Asteriades MD, FRCS

Zachos Zachariadis MD, DO

Edited by:

Penelope de Politis, MD

A 9-year-old boy with monocular vision presented with reduction of visual acuity in his previously normal eye.

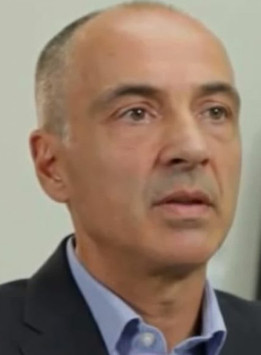

Figure 1: Spectralis SD-OCT (Heidelberg Engineering®) of the left eye featuring a macular tuft and loss of foveal contour.

Case History

A 9-year-old Caucasian boy was diagnosed with an optic nerve meningioma in the right eye (RE) 4 years ago. Further investigation had revealed a second neural tumor elsewhere, leading to the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 2. At the time of diagnosis, the patient underwent a decompressive procedure for the optic neural tumor – fenestration – but the condition ultimately progressed to optic nerve atrophy in that eye.

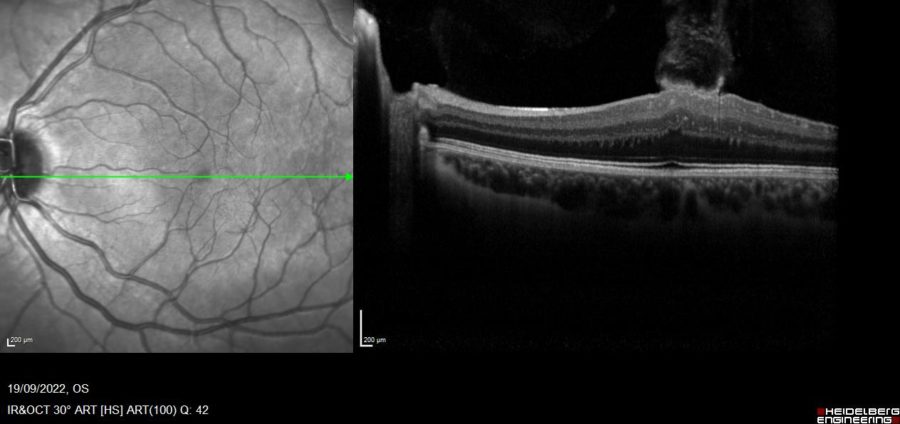

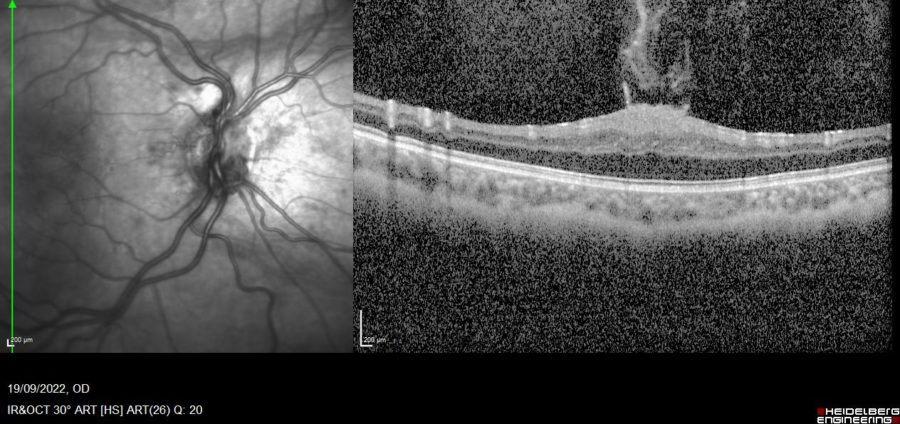

Upon referral for ophthalmologic examination, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in the left eye (LE) was 7/10. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) of the LE displayed a flame-shaped macular tuft of epiretinal tissue projecting into the vitreous chamber (Figure 1). An identical lesion as found in the RE (Figure 2), aside from an atrophic optic papilla (Figure 3).

Figure 2: SD-OCT of the RE displaying an atrophic optic papilla and a macular tuft of epiretinal tissue projecting into the vitreous chamber. Notice the loss of foveal depression, increased retinal thickness, absence of cystoid spaces or retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) disruption, and preservation of the inner segment-outer segment junction.

Figure 3: SD-OCT of the RE showing distortion of the optic papilla and peripapillary atrophy.

Differential Diagnosis

- combined hamartoma of the retina and RPE

- proliferative vitreoretinopathy

- tractional retinal detachment

- familial exudative vitreoretinopathy

- non-specific epiretinal membrane (e.g., idiopathic, traumatic, uveitic)

The characteristic aspect of the epiretinal membrane, in a flame-shaped disposition directed towards the vitreous center, is considered specific and diagnostic of neurofibromatosis type 2.

Additional History

A careful assessment of the pediatric and developmental status of the patient was conducted. Considering the child’s stable general health condition and absence of significant behavioral distress, a conservative approach was discussed and decided along with his parents. Close interdisciplinary monitoring for disease progression and eventual necessary interventions will be kept for the moment.

Discussion and Literature

Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) is an autosomal dominant, single-gene disorder, caused by either sporadic — more frequent — or inherited pathogenic variants of the NF2 gene on chromosome 22. The incidence of NF2 is reported to be as high as 1 in 25,000 individuals in 2 large population studies — in Finland and in England. NF2 is characterized by the development of schwannomas — especially vestibular —, meningiomas, and ependymomas. The classical phenotype of NF2 also includes ocular features such as cataracts, retinal abnormalities — retinal hamartomas with or without RPE involvement —, epiretinal membranes (ERMs), paralytic strabismus, optic disk gliomas, and optic nerve sheath meningiomas.

Symptoms and signs relating to vestibular schwannomas are not always the presenting feature in NF2, even less so in children, who more commonly manifest eye, skin, or neurological problems. The detection of ocular features can aid in the clinical diagnosis of NF2 and prompt early genetic testing. The recent identification of numerous retinal abnormalities by SD-OCT suggests that the retinal features of NF2 may be more common than previously thought. They are also more common in more severe NF2 genotypes, as captured by the UK NF2 Genetic Severity Score — 1. tissue mosaic; 2A. mild classic; 2B. moderate classic; 3. severe.

SD-OCT imaging-based studies have been able to characterize retinal findings in patients with NF2 in greater detail than previously possible and to identify novel retinal abnormalities such as retinal tufts specific to NF2. These are projections of tissue extending from the inner retina into the vitreous and occur far more commonly than typical ERMs in these patients. Often resembling horns or flames, they are thought to be either focal ERMs or small elevations of retinal tissue, termed subclinical hamartomas due to their small size, with similar histopathologic origin — from glial cells. Increased central macular thickness is another feature of the ocular abnormalities associated with NF2, apparently less prominent when optic atrophy is present.

Potentially treatable sources of damage to vision must be identified early and treated effectively to retain useful vision throughout life. There are no standard guidelines for treating NF2 patients with ERMs. Observation and surgical intervention are the current treatment choices. Macular tufts can be peeled through microincision vitrectomy surgery (MIVS) but may pose a challenge when deeply integrated into the retina as retinal damage or tears may ensue. Even with complete removal of the ERM, the abnormally thickened macula may remain unchanged even after years postoperatively. Postoperative visual outcomes have been reported for only 3 cases so far. Although surgery can improve retinal sensitivity and visual acuity, the potential surgical risks related to vitreoretinal surgery in pediatric eyes require careful consideration on a case-by-case basis. A significant decrease in quality of life, as impairment for regular activities or performance at school, may justify the decision for a surgical intervention.

Insights into the molecular biology of NF2 have shed light on the etiology and variable severity of the disease and suggested numerous putative molecular targets for therapeutic intervention. Chromosome 22q12.1, whose mutation is involved in the pathogenesis of NF2, encodes for a protein called merlin or schwannomin, in the merlin pathway. Multiple additional pathways have been identified, and pre-clinical and clinical investigation of novel therapeutic agents including FAK, EGFR, cMET, PD-1/PD-L1, and VEGFR inhibitors is underway. Biological treatment strategies aimed at multiple tumor regression or arrest of progression — employing Lapatinib, Erlotinib, Everolimus, Picropodophyllin, OSU.03012, Imatinib, Sorafenib, and Bevacizumab — are under research.

Keep in mind

- Initial manifestations of NF2 differ between children and adults. NF2-specific ophthalmological findings can be diagnostic for the disease.

- Early-onset NF2 is associated with higher severity and marked disease progression, especially in the presence of characteristic ocular abnormalities.

- Young patients with NF2 must be carefully monitored for timely detection of treatable manifestations and preservation of visual function throughout life.

References

- Emmanouil, B., Wasik, M., Charbel Issa, P., Halliday, D., Parry, A., & Sharma, S. M. (2022). Structural Abnormalities of the Central Retina in Neurofibromatosis Type 2. Ophthalmic research, 65(1), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1159/000519143

- Waisberg, V., Rodrigues, L. O., Nehemy, M. B., Frasson, M., & de Miranda, D. M. (2016). Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Findings in Neurofibromatosis Type 2. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 57(9), OCT262–OCT267. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-18919

- Sisk, R. A., Berrocal, A. M., Schefler, A. C., Dubovy, S. R., & Bauer, M. S. (2010). Epiretinal membranes indicate a severe phenotype of neurofibromatosis type 2. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.), 30(4 Suppl), S51–S58. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181dc58bf

- Bosch, M. M., Boltshauser, E., Harpes, P., & Landau, K. (2006). Ophthalmologic findings and long-term course in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. American journal of ophthalmology, 141(6), 1068–1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2005.12.042

- Kunikata, H., Nishiguchi, K. M., Watanabe, M., & Nakazawa, T. (2022). Surgical outcome and pathological findings in macular epiretinal membrane caused by neurofibromatosis type 2. Digital journal of ophthalmology : DJO, 28(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.5693/djo.02.2021.06.001

- Ruggieri, M., Iannetti, P., Polizzi, A., La Mantia, I., Spalice, A., Giliberto, O., Platania, N., Gabriele, A. L., Albanese, V., & Pavone, L. (2005). Earliest clinical manifestations and natural history of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) in childhood: a study of 24 patients. Neuropediatrics, 36(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-837581

- Coy, S., Rashid, R., Stemmer-Rachamimov, A., & Santagata, S. (2020). An update on the CNS manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 2. Acta neuropathologica, 139(4), 643–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-019-02029-5

- Ruggieri, M., Praticò, A. D., & Evans, D. G. (2015). Diagnosis, Management, and New Therapeutic Options in Childhood Neurofibromatosis Type 2 and Related Forms. Seminars in pediatric neurology, 22(4), 240–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2015.10.008

- Waisberg, V., Rodrigues, L., Nehemy, M. B., Bastos-Rodrigues, L., & de Miranda, D. M. (2019). Ocular alterations, molecular findings, and three novel pathological mutations in a series of NF2 patients. Graefe’s archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie, 257(7), 1453–1458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-019-04348-5

- Painter, S. L., Sipkova, Z., Emmanouil, B., Halliday, D., Parry, A., & Elston, J. S. (2019). Neurofibromatosis Type 2-Related Eye Disease Correlated With Genetic Severity Type. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society, 39(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNO.0000000000000675