Presented by: Koutsiouki Chrysa, MD

Edited by: Penelope Burle de Politis, MD

A 44-year-old woman was referred for investigation of subacute visual loss and optic disc edema in both eyes.

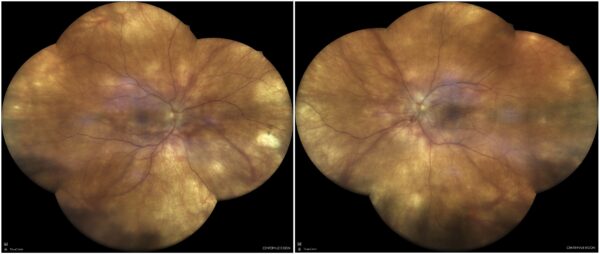

Figure 1: Fundus color photograph (iCare confocal high-resolution ultra-widefield Truecolor Centervue EIDON®) showing a hypopigmented fundus and optic disc edema in both eyes, along with mild vitritis. Deep, small, yellow nummular lesions can be noted in the mid periphery bilaterally (Dalén-Fuchs nodules).

Case History

A 44-year-old Caucasian woman was referred for multimodal fundus imaging as part of the propaedeutic evaluation of bilateral papilledema. Her symptoms had begun 9 months earlier and included transient vision loss, floaters, photophobia, headaches, and a “heavy head” sensation. She also reported some neck stiffness and tinnitus. Her past medical history was unremarkable except for alopecia and vitiligo. Her family history was negative for ophthalmic diseases. Upon examination, her corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) was 6/10 bilaterally, with discrete against-the-rule astigmatism in both eyes (BE). The eyes were calm but biomicroscopy revealed subtle inferior keratic precipitates (KPs), cells in the anterior chamber (1+), and flare (1+). Intraocular pressure (IOP) was within the normal range bilaterally. Fundoscopy showed vitritis (1+), a hypopigmented fundus, blurred optic disc margins, and Dalén-Fuchs nodules in BE (Figure 1).

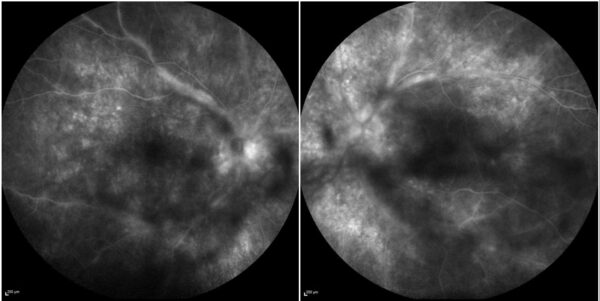

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) was consistent with bilateral subclinical optic disc edema. Enhanced depth imaging (EDI) OCT detected significantly increased choroidal thickness, respectively 700 μm in the right eye (RE) and 750 μm in the left eye (LE). Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) revealed numerous pinpoint hyperfluorescent spots and optic nerve head edema, periphlebitis, and diffuse capillary leakage in BE, more pronounced on the left (Figure 2).

Figure 2: FFA (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering®) showing multiple pinpoint hyperfluorescent spots and diffuse capillary dye leakage, along with periphlebitis and a “hot disc” in both eyes.

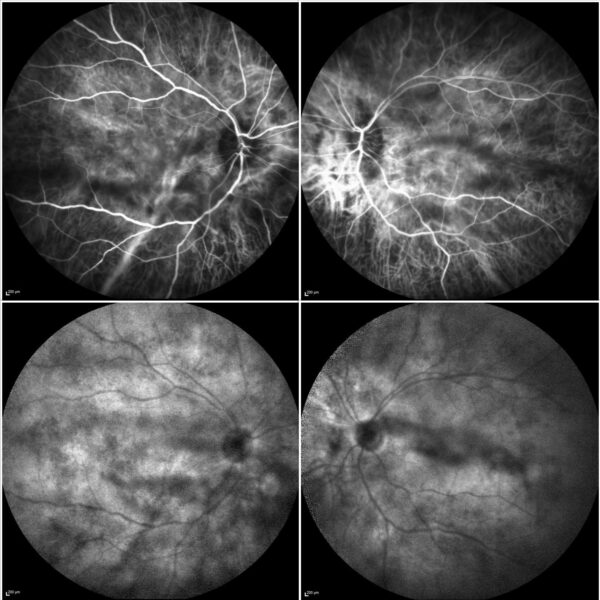

Indocyanine green angiography (ICG-A) showed prominent choroidal vessels in the early frames and multiple hypocyanescent spots in BE (Figure 3).

Figure 3: ICG-A (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering®) of both eyes displaying prominent choroidal vessels in the early frames (top) and numerous hypocyanescent spots (Dalén-Fuchs nodules) in the late frames (bottom).

Additional History

The patient had undergone neurological evaluation and was initially diagnosed with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and managed with acetazolamide, with partial symptomatic relief. However, the ocular and multimodal imaging findings favored the diagnosis of Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) syndrome.

Treatment was started with oral tapered prednisone, calcium, and vitamin D. Additional workup with a full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs), Quantiferon, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), and a chest radiogram was requested. A follow-up was scheduled in 4 weeks’ time for reevaluation and start of mycophenolate mofetil.

Differential Diagnosis of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome

- posterior scleritis

- benign reactive uveal lymphoid hyperplasia

- diffuse melanoma

- choroidal involvement in leukemia or lymphoma

- sympathetic ophthalmia

- tuberculosis

- syphilis

- sarcoidosis

- acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE)

- multifocal choroiditis

- malignant systemic hypertension

- Cogan syndrome

- multiple sclerosis

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with headache, blurring of vision, and optic nerve head swelling, which often leads to the suspicion of raised intracranial pressure. Absence of past ocular trauma or surgery, bilateral diffuse choroiditis, auditory and neurological manifestations, and integumentary findings help distinguish VKH from other pathological entities.

Discussion and Literature

Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) syndrome is a systemic autoimmune disease in which the main target is melanin-containing cells present in the eye, meninges, ear, and skin, leading to the loss of melanocytes and subsequent depigmentation. It accounts for 6–8% of all uveitis in Asia. The female-to-male ratio of the disease is around 2:1 and the age of onset is usually between the second and fifth decades of life. Although the etiology of VKH is still not completely known, numerous studies indicate an autoimmune pathophysiology. The HLA-DRB1*0405 gene variant (allele) plays an important role in the pathogenesis of VKH, rendering carriers more susceptible to the disease.

In 1906, Alfred Vogt, an Ophthalmology resident in Switzerland, described a dark-complexion 18-year-old with premature whitening of eyelashes and subacute iridocyclitis. Einosuke Harada, in 1926, reported cases with acute bilateral posterior uveitis with exudates followed by diffuse depigmentation and the characteristic sunset glow fundus appearance. Poliosis and vertigo were accompanying symptoms. In 1929, Yoshizo Koyanagi described the precise natural course of the untreated disease, including the prodromal phase, the acute phase with posterior segment involvement, the convalescent phase, and the auditory and integumentary manifestations.

The systemic manifestations of VKH include meningismus (generally in the form of headaches), dysacusis, poliosis, and vitiligo, but the most dire clinical feature is the ocular involvement – a bilateral, diffuse, chronic panuveitis. The primary ocular pathology is diffuse thickening of the uveal tract during the acute phase, caused by non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. In the acute phase, retinal detachment with collection of subretinal fluid most likely results from alterations in the RPE as an “upstream” effect of choroidal compromise. Focal collections of lymphocytes, pigment-laden macrophages, epithelioid cells, and proliferated retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) represent the Dalén-Fuchs nodules.

The clinical course of VKH disease follows 4 phases: prodromic, uveitic, convalescent, and recurrent (chronic). The prodromal stage features flu-like and neurologic signs and symptoms. The cerebrospinal fluid may reveal pleocytosis in 80% of cases within one week of disease onset. An acute uveitic phase follows within a few days, and is characterized by bilateral, usually symmetric, diffuse uveitis, hyperemia and edema of the optic disc, and serous retinal detachment of varied extent. The inflammation may extend to the anterior segment. After several weeks, depigmentation of the integument and choroid may occur, characterizing the convalescent phase. Approximately two-thirds of patients eventually develop a chronic phase, mainly characterized by recurrent episodes of anterior uveitis. Complications may include cataract, glaucoma, subretinal fibrosis, and choroidal neovascularization.

Multimodal fundus imaging modalities – retinography, fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography, optical coherence tomography, and ultrasound – as well as functional tests – electroretinogram and visual field testing – play an important role in diagnosis, severity grading, and disease monitoring. Advanced imaging technology also contributes to terminology standardization and to the understanding of VKH pathophysiology.

Prompt and adequate therapy in the initial phase may reduce subsequent recurrences and alter the course of diffuse and focal fundus depigmentation, as well as the incidence of extraocular manifestations. Early high-dose systemic corticosteroids remain the gold standard initial management of VKH, though immunomodulatory or immunosuppressant medication – cyclosporine A, antimetabolites, biological agents – and even peribulbar depot steroids may be added for maintenance and treatment of refractory cases. There is presently a preference among uveitis specialists to use both immunomodulatory therapy (IMT) and systemic corticosteroids for the first episode of acute disease, as recent studies show that the association of steroidal and non-steroidal immunosuppression induces long-term remission and even cure of VKH disease.

Due to advances in diagnostic and therapeutic methods, most VKH patients now have a favorable visual prognosis, with a final visual acuity better than 20/40 in about 60% of cases. Inadequate treatment (delayed, in suboptimal dose, or with early interruption) and severe initial disease are the main factors associated with worse prognosis.

Keep in mind

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome is an autoimmune condition featuring ocular and systemic findings caused by inflammation targeting pigmented tissues.

- VKH can easily masquerade as IIH by presenting with severe headache, blurred vision, and bilateral optic disc edema.

- Combination of steroidal and non-steroidal immunosuppression is required to treat initial-onset acute VKH disease and prevent chronic evolution.

References

- Fang W & Yang P (2008). Vogt-koyanagi-harada syndrome. Current eye research, 33(7), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/02713680802233968

- Sakata VM, da Silva FT, Hirata CE, de Carvalho JF & Yamamoto JH (2014). Diagnosis and classification of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Autoimmunity reviews, 13(4-5), 550–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.023

- Ng JY, Luk FO, Lai TY & Pang CP (2014). Influence of molecular genetics in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Journal of ophthalmic inflammation and infection, 4, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12348-014-0020-1

- Khairallah AS (2014). Headache as an initial manifestation of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society, 28(3), 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjopt.2013.10.003

- Nichani P, Christakis PG & Micieli JA (2021). Headache and Bilateral Optic Disc Edema as the Initial Manifestation of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society, 41(1), e128–e130. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNO.0000000000000917

- Shoughy SS & Tabbara KF (2019). Initial misdiagnosis of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society, 33(1), 52–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjopt.2018.11.006

- Hussain A & Khurana R (2021). Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome: A Diagnostic Conundrum. Cureus, 13(12), e20138. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.20138

- Song M, Baek SH, Lee SU, Yu S & Kim JS (2021). Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease – A diagnostic pitfall for neurologists. eNeurologicalSci, 26, 100390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensci.2021.100390

- Choo CH, Acharya NR & Shantha JG (2023). Common practice patterns in the diagnosis and management of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome: a survey study of uveitis specialists. Frontiers in ophthalmology, 3, 1217711. https://doi.org/10.3389/fopht.2023.1217711

- Erba S, Govetto A, Scialdone, A & Casalino G (2021). Role of optical coherence tomography angiography in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. GMS ophthalmology cases, 11, Doc06. https://doi.org/10.3205/oc000179

- Wu W, Wen F, Huang S, Luo G & Wu D (2007). Indocyanine green angiographic findings of Dalen-Fuchs nodules in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Graefe’s archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology, 245(7), 937–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-006-0511-3

- Karti O, Ayhan Z & Saatci OA (2025). Use of Imaging Modalities in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease: An Overview. Ceske oftalmologicke spolecnosti a Slovenske oftalmologicke spolecnosti, 81(5), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.31348/2025/26

- Tayal A, Daigavane S & Gupta N (2024). Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease: A Narrative Review. Cureus, 16(4), e58867. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.58867

- Lodhi SA, Reddy JL & Peram, V (2017). Clinical spectrum and management options in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.), 11, 1399–1406. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S134977

- Herbort CP Jr, Abu El Asrar AM, Takeuchi M, Pavésio CE, Couto C, Hedayatfar A, Maruyama K, Rao X, Silpa-Archa S & Somkijrungroj T (2019). Catching the therapeutic window of opportunity in early initial-onset Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada uveitis can cure the disease. International ophthalmology, 39(6), 1419–1425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-018-0949-4