Presented by: Lampros Lamprogiannis MD, MSc, PhD, FEBOphth

Edited by: Penelope de Politis, MD

An 11-year-old girl presented with epiphora on the left eye for 6 months.

Figure 1: Unilateral painless epiphora on the left eye, without primarily noticeable ocular changes.

Case History

A 11-year-old Caucasian girl was referred for presenting lacrimation on the left for 6 months. She had no previous history of ophthalmic disorders. Family history was negative for severe ocular problems. Upon examination, uncorrected distance visual acuity was 10/10 bilaterally with emmetropia. There were no lid abnormalities and ocular surface assessment was unremarkable. Mild anisocoria was noticed, and the left pupil displayed a slow reflex response to light stimulation. Ocular motility evaluation revealed exophoria and limited excursion during upward and downward gaze on the left.

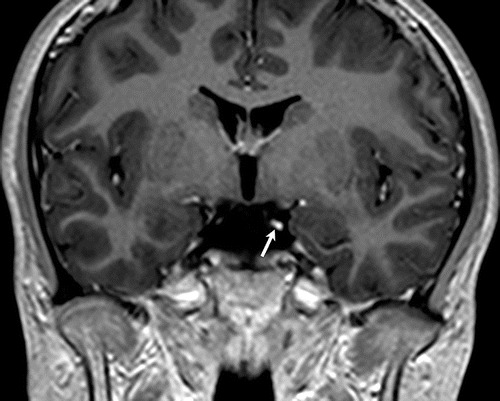

Investigation proceeded with a full neurological workup. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging showed focal thickening and post-contrast enhancement of the left oculomotor nerve (as exemplified in Figure 2).

Figure 2: Coronal 3D T1-weighted post-contrast MR image showing focal thickening and enhancement of the left oculomotor nerve (arrow).

Additional History

The patient had suffered a blunt trauma to the head at the age of 4. A subdural hematoma was detected on that occasion and a diagnosis of partial dural venous thrombosis was made. At the time of referral for ophthalmologic investigation, the intracranial hemovascular lesions had already been absorbed and the girl was no longer on any medications.

Upon further questioning, the patient’s parents informed that the tearing was most evident while the girl was eating. At some point during the follow-up visit, the child was given a candy and started chewing. A few seconds later, lacrimation on the left automatically started, confirming the clinical diagnosis of crocodile tears syndrome, in her case secondary to left III cranial nerve palsy.

A complementary oculoplastic evaluation was conducted, and management with botulinum toxin type A injection to the lacrimal gland was indicated (as illustrated in Figure 3). Marked reduction of gustatory lacrimation was noticeable 5 days after the first application.

Figure 3: Transconjunctival injection of botulinum toxin A into the temporal lobe of the left lacrimal gland. The patient is asked to look inferonasally (away from the affected lacrimal gland).

Differential Diagnosis of Crocodile Tears Syndrome in Children

- VII cranial nerve palsy

- dacryocystocele

- congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- punctal or canalicular agenesis

- punctal occlusion

- conjunctivitis

- foreign body

- keratitis

- epiblepharon or entropion

- ectropion

- distichiasis

- trichiasis

- glaucoma

- iritis

The differential diagnosis of crocodile tears syndrome includes all forms of epiphora. Diagnosis is mostly clinical, but neurological imaging is often required to identify the anatomic site of nerve injury.

Discussion and Literature

Epiphora is a common complaint in ophthalmological practice. Causes of epiphora are related either to secretory disturbances or to problems in the excretory lacrimal system. Accurate detection of primary and secondary causes is crucial to define the management strategy. Normal lacrimation can be basal (basic tear production), reflex (to surface or photo-stimulation), or psychic (emotional). On the other hand, epiphora can be subdivided into gustatory (“crocodile tears” caused by aberrant nerve regeneration), reflex (reactive tear production caused by any ocular surface trauma or abnormal stimulation), obstructive (punctal, canalicular, lacrimal sac or lacrimal duct occlusion), and hypersecretory (excessive production of tears, a very rare condition).

The reference to crocodiles comes from literary and mythological sources which allude to crocodilians weeping while eating their prey. Physiologically, it is thought that crocodiles shed tears during mastication due to mechanical stimulation by the pressure of air pushed into their sinuses. Another explanation is that crocodiles are rough eaters, which too could stimulate their lacrimal glands. The fact is that reptiles and many birds have specialized lacrimal glands which produce oily tears, a protective mechanism developed during their evolutive re-adaptation to the aquatic environment.

Chronic painless unilateral epiphora associated with eating, drinking, chewing, talking, laughing, yawning, or simply opening the mouth is highly suggestive of crocodile tears syndrome. Also called Bogorad’s syndrome, the condition is more commonly associated with facial (VII cranial) nerve dysfunction and is caused by aberrant nerve regeneration. In that case, nerve branches that would normally go to the parotid gland regenerate towards the lacrimal gland. Whichever the involved cranial nerve is, hyperlacrimation usually develops 6 months or more after the original nerve palsy. Neurologic examination focused on the intracranial nerves, with assessment of intra and extraocular innervation can provide clues to the damaged nerve.

The motor nucleus of the oculomotor (III) nerve is located at the anterior aspect of the periaqueductal gray matter at the superior colliculi level in the midbrain. The nerve exits the midbrain into the interpeduncular cistern between the superior cerebellar artery and posterior cerebral artery, then runs anteroinferiorly in the prepontine cistern and continues along the superolateral wall of the cavernous sinus, finally entering the orbit via the superior orbital fissure. Damage to the nerve can occur at any segment of this pathway.

Oculomotor nerve palsy (ONP) is uncommon in children, and the most common causes are congenital, followed by trauma, tumor, vascular problems, and infection. Isolated ONP due to mild closed head trauma is a rare entity. Traumatic oculomotor nerve injury is usually caused by severe head trauma and is generally associated with other findings such as basilar skull fracture, orbital injury, or subarachnoid hemorrhage. In the absence of such abnormalities, a routine brain MRI may not always be positive. Therefore, an MRI specifically dedicated to oculomotor nerve imaging, using FS T2WI and high-resolution 3D sequences, should be preferred. MRI is expected to reveal a thickened affected nerve, with an enhanced post-contrast signal for up to 4 years after symptoms onset. Neuroimaging is also useful in excluding compressive lesions, such as aneurysms or intracranial masses.

Aberrant regeneration of the III nerve is most commonly due to nerve damage by trauma. The full-blown features of this syndrome (horizontal gaze-eyelid synkinesis, pseudo-Graefe sign, limitation of elevation and depression of the eye with retraction of the globe on attempted vertical movements, adduction of the involved eye on attempted elevation or depression, pseudo-Argyll Robertson pupil and absent vertical optokinetic response) may or may not be present. The incidence of aberrant regeneration of the third nerve after acute injury is reported to be 15%. Because symptoms may start long after the initial injury, causal association is tricky, and diagnosis may be delayed by several years.

Gustatory lacrimation is best measured and monitored by the thread test (modified Schirmer test) during taste stimulation (with a sweet-sour candy, for example). Lacrimation on the side of the lesion before and after taste stimulation is compared. After stimulation, an increase in lacrimation on the affected side is likely to be observed.

Different treatment options for gustatory lacrimation have been suggested, from topical adrenergic block to the lacrimal gland with topic guanethidine solution, to systemic treatment with propantheline bromide or pyridostigmine by mouth. Topical instillation of homatropine hydrobromide for secretomotor nerve blockade has also been proposed, but the side effects of these pharmacological modulations outweigh their therapeutic outcome. Surgical options include excision or subtotal resection of the palpebral lobe of the lacrimal gland, cutting of the chorda tympani nerve, denervation of the lacrimal gland either by dissection or diathermy, sphenopalatine ganglion blockade by alcohol or cocaine, and vidian neurectomy. Nonetheless, these options are redundant, drastic, and have persistent side effects such as total ablation of the lacrimal gland resulting in permanent dry eye. Current management is aimed at the severity of hyperlacrimation and the patient’s needs. Mild cases are generally managed by counseling and regular monitoring only.

The most widely accepted intervention for crocodile tears syndrome is botulinum toxin injection into the lacrimal gland. Botulinum toxin is an acetylcholine release inhibitor and acts at the neuromuscular junction by stopping transmission along the aberrantly regenerated parasympathetic nerve fibers to the affected gland. Botulinum toxin has been used to treat other localized autonomic disorders as well, such as axillary or palmar hyperhidrosis, Frey syndrome, and even other forms of refractory epiphora. The usual dose is 2.5 units per application, and higher doses seem to have no additional benefit in terms of efficacy or duration. Results can be noticed within a week after injection and can last for about 6 months. The substance can be administered transcutaneously or transconjunctivally into the temporal lobe of the gland, the latter route having lesser complications. Complications like ptosis, extraocular muscle weakness, and xerophthalmia are infrequent, minor and reversible. Treatment can be repeated when lacrimation reoccurs, and long-term re-treatments have been proven to have a stable efficacy-safety profile.

Keep in mind

- Though usually associated with VII nerve palsy, crocodile tears syndrome is a possible late complication of head injury involving the III cranial nerve.

- High resolution-MRI directed to the suspected involved nerve is the best complementary tool in the differential diagnosis of gustatory lacrimation.

- Application of botulinum toxin to the lacrimal gland is currently the safest and most effective available therapy for Bogorad’s syndrome.

References

- Patel J, Levin A & Patel BC (2021). Epiphora. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557449/

- Modi P & Arsiwalla T (2021). Crocodile Tears Syndrome. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525953/

- Bogorad FA (1979). The symptom of crocodile tears. Introduction and translation by Austin Seckersen. Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences, 34(1), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/xxxiv.1.74

- Yagi N & Nakatani H (1986). Crocodile tears and thread test of lacrimation. The Annals of otology, rhinology & laryngology. Supplement, 122, 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/00034894860950s103

- Hwang JY, Yoon HK, Lee JH, Yoon HM, Jung AY, Cho YA, Lee JS & Yoon CH (2016). Cranial Nerve Disorders in Children: MR Imaging Findings. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc, 36(4), 1178–1194. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2016150163

- Lueck CJ (2011). Infranuclear ocular motor disorders. Handbook of clinical neurology, 102, 281–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-52903-9.00017-0

- Kim E & Chang H (2013). Isolated oculomotor nerve palsy following minor head trauma : case illustration and literature review. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society, 54(5), 434–436. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2013.54.5.434

- Im Y & Kim JR (2021). MRI Findings of Isolated Oculomotor Nerve Palsy after Mild Head Trauma in a Pediatric Patient: Case Report. Pediatric neurosurgery, 56(1), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1159/000512876

- Chua HC, Tan CB & Tjia H (2000). Aberrant regeneration of the third nerve. Singapore medical journal, 41(9), 458–459. http://www.smj.org.sg/sites/default/files/4109/4109cr2.pdf

- Sayed SA & Rabea M (2013). Misdirection (aberrant regeneration) of the third cranial nerve. J Egypt Ophthalmol Soc 2013;106:150-2. http://www.jeos.eg.net/text.asp?2013/106/3/150/127361

- de Oliveira D, Gomes-Ferreira PH, Carrasco LC, de Deus, CB, Garcia-Júnior IR & Faverani LP (2016). The Importance of Correct Diagnosis of Crocodile Tears Syndrome. The Journal of craniofacial surgery, 27(7), e661–e662. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000003006

- Lee, A. G., Lee, S. H., Jang, M., Lee, S. J., & Shin, H. J. (2021). Transconjunctival versus Transcutaneous Injection of Botulinum Toxin into the Lacrimal Gland to Reduce Lacrimal Production: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Toxins, 13(2), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13020077

- Kyrmizakis DE, Pangalos A, Papadakis CE, Logothetis J, Maroudias NJ & Helidonis ES (2004). The use of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of Frey and crocodile tears syndromes. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery: official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, 62(7), 840–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2003.09.015

- Wojno TH (2011). Results of lacrimal gland botulinum toxin injection for epiphora in lacrimal obstruction and gustatory tearing. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery, 27(2), 119–121. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0b013e318201d1d3

- Barañano DE & Miller NR (2004). Long term efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin A injection for crocodile tears syndrome. The British journal of ophthalmology, 88(4), 588–589. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2003.029181

- Jeffers, J., Lucarelli, K., Akella, S., Setabutr, P., Wojno, T. H., & Aakalu, V. (2021). Lacrimal gland botulinum toxin injection for epiphora management. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 1–12. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2021.1966810